Is having competing elites the best that we can hope for in a democracy?

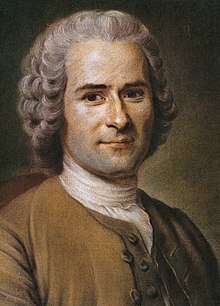

The views of Joseph Schumpeter offer an interesting perspective on democracy. He is of elitist thought and believes that only elites in society should govern. Schumpeter sets out a credible argument as to why he believes this, looking at the role of the citizen and the way a democracy should be run. Schumpeter believes that the only purpose of democracy in society is to aid in decision making. In many ways, the democratic theory set out by Schumpeter can be likened to the model that is representative democracy. This is because the representative view sees one individual being allowed to represent many in a political system, the individual being the elite as in Schumpeter’s ideals. It will also be important to offer the contrasting views of philosophers such as Burke and crucially Rousseau, a proponent of direct democracy. This essay will attempt to balance the argument between Schumpeterian elitism and the more direct approach to democracy but also to examine how closely related representative democracy is to Schumpeter’s ideals.

The Austrian Joseph Schumpeter worked and lived for most of his life in the USA and is considered as one of the major political thinkers in the twentieth century, with regards to economics and most prominently democracy. His most famous work written in 1942, ‘Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy’ debates how socialism and democracy could coexist but also outlines his theory on democracy or as he claims the ‘theory of competitive leadership’ (Swedberg, 1991). Schumpeter therefore lays claim to being an elitist; that is to say he favours the rule of knowledgeable elites in society. He shares this view with Max Weber who determined a system of ‘competitive elitism’, the model that Schumpeter’s theory on democracy is closely aligned to (Held, 1987). It would be inaccurate however to brandish all elitists as one and the same as elitist thought has come about at many different points in history, where the meaning of elitism might be slightly different given the relevant contexts. Schumpeter also claims to be a realist in outlook, a point that cannot be contested given that all his opinions are based on fact. Wedberg adds, “… but he also took a certain pride in not letting his prejudices interfere with his better judgement” (Swedberg, 1991, p. 141).

Representative democracy is the core foundation for Schumpeter’s theory on democracy and is still present today in varied forms all around the world. It is often seen as a response to a more direct system of democracy as Held states, “Representative government overcomes the excesses of pure democracy because elections themselves force a clarification of public issues…” (Held, 1987, p. 64). The ideal behind representative democracy is that one person or politician should be able to represent many people in an institution such as a parliament. It could be suggested that these people are similar to the elites of which Schumpeter speaks of and could enact any of the three main underpinnings of representative democracy as single entities. These are the mandate to govern, the ability and power to speak on behalf of others and the literal representation of people like themselves, this could be racial or gender specific for example. In contemporary society, constituents rely on mandated representatives to bring their views and specific topics to Parliament. Although as Phillips says, “Democracy as we know it emerged through a dual shift – from direct to representative democracy, and from a politics of the common good to a politics of individual protection” (Phillips, 1993, p. 124). Many of today’s mp’s are influenced by greater powers such as their party and the opinion of the general public. Just because a topic may be important to a particular constituency doesn’t mean it is to the rest of the country or that the issue is in accordance to the party line. This is so often a critique of singular rulers and so can be applied to a Schumpeterian argument. Pitkin explains that, “The representative must act independently; his action must involve discretion and judgement; he must be the one who acts” (Pitkin, 1967, p. 209). The ultimate decision on whether to raise an issue to parliament is left down to one single individual who may have an alternative opinion on the matter and therefore does not fairly represent the majority. Edmund Burke, seen as an elitist and as one of the founding fathers of conservative thought, picks up on this critique of mandated representatives. Pitkin states, “For Burke, political representation is the representation of interest, and interest has an objective, impersonal, unattached reality” (Pitkin, 1967, p. 168). Burke, who despite being known to show a disregard for public opinion, claims that this system would create a parliamentary battleground where nothing gets done, which in turn could prove problematic for the interests and unity of a country. Despite this view, the representative argument still remains strong especially when taking into account contemporary politics. As a nation we appear broadly happy with the level of democracy that we currently have. It also allows the electorate a certain platform on which to scrutinise the government. This is mostly through media outlets and question sessions for which representatives of each major party can display their party policies. Thus, a Schumpeterian argument that claims that elitist rule is the best we can hope for, certainly does have contemporary relevance and can be likened towards today’s society.

Schumpeter’s argument does well to build on the basic underpinnings of representative democracy despite certain critiques on the core foundations of the system. For Schumpeter, democracy is simply a method or a way in which to arrive at a political decision. At his time of living, Schumpeter thought that political was too normative and did not represent the reality of what was going on in society. Wedberg says, “Schumpeter, as we know, develops his own theory of democracy in contrast to what he called ‘the classical doctrine of democracy’” (Swedberg, 1991, p. 162). He also claims that democracy should be fought out between just two political entities. That is to say two political parties and its leaders or, as Schumpeter would argue, political elites. Schumpeter’s view on the role of the citizen in a democratic society is what is often thought to set him apart. Similarly to Burke, Schumpeter believes that citizens do not have credible enough opinions to allow them access to directly influence democracy. Instead, the role of the citizen is simply to choose which one of the two available candidates they prefer and give them a mandate to govern. According to Schumpeter, “Democracy does not mean and cannot mean that the people actually rule in any obvious sense of terms ‘people’ and ‘rule’. Democracy means only that the people have the opportunity of accepting or refusing the men who are to rule them.… Now one aspect of this may be expressed by saying that democracy is the rule of the politician.” (Schumpeter, 1942, pp. 284-5). As such, Schumpeterian democracy avoids any left wing ideals that would prefer more public participation. Instead the elites in a Schumpeterian society would govern on behalf of the people, as in representative democracy, where, as Schumpeter claims ‘democracy is the rule of the politician’ (Held, 1987). That is to say that the populace should have no fear of an elitist society and that Schumpeterian democracy will always avoid tyrannical leaders as the public vote will always have the initial choice between two candidates. Held states, “The development of competing parties irreversibly changes the nature of parliamentary politics. Party machines sweep aside traditional affiliations and establish themselves as centres of loyalty, displacing others as the key basis of national politics” (Held, 1987, p. 156). Schumpeter argues that once this choice is made, politicians or the elites left in charge should be allowed to govern as they see fit. This view could be likened to Plato and his theory of the philosopher kings as Schumpeter believes that future decisions should be left to those who know best and have the greatest knowledge. Held comments on Plato, “Plato’s position, in brief, is that the problems of the world cannot be resolved until philosophers rule; for only they, when fully educated and trained, have the capacity to harmonize all elements of human life under ‘the rule of wisdom’” (Held, 1987, p. 31). Although Schumpeter does not claim that elites have a god given right of power in the same way Plato claims, Schumpeter does claim though that an elitist form of democracy is the best we can hope for. He argues this not simply because it favours those seen as greatest in society but because democracy does not imply that people should have direct access to power, just that they can choose who has it. It should be important to the people thereafter that society is run effectively and thus, those who have the most knowledge should govern to ensure success.

The alternative to a representative form of government such as Schumpeter’s would be to involve more people in politics and increase participation. This brings the theories on democracy back to Schumpeter’s rather specific critique on what democracy is and what he believes the alternative should be. Nevertheless, direct democracy is a well known and credible model of democracy and can be used to further critique Schumpeter and representative democracy. As Dahl argues, “These institutions of representative democracy removed government so far from the direct reach of the demos that one could reasonably wonder, as some critics have, whether the new system was entitled to call itself by the venerable name of democracy” (Dahl, 1989, p. 30). Direct democracy offers up a form of democracy in its purest form and allows for a completely fair society. In a direct democracy, political participation would be of vital importance in order to come to decisions which could affect the lives of the populace. This is in stark contrast to today’s society which offers little in the way of participation for the ordinary member of the community. Furthermore as Rousseau argues, there would be increased deliberation to ensure the safe passage of changes to constitutional law; a power which would be vested in the people. Medding argues, “Democracy, it is claimed, demands the direct participation of all citizens in decision making, with issues being decided after careful reasoned, informed, and widespread public discussion” (Medding, 1969, p. 642). Issues of importance would be weighted in accordance to the amount of support showed for it by the people. Boucher says of Rousseau, “He argued against the principle of deputies, or representatives, ridiculing the British system in being free only at the time of elections. He argued that sovereignty cannot be represented…” (Boucher, 2009, p. 275). Above all a direct democracy would introduce at least a sense of equality which would allow everyone in a society to be heard. The Schumpeterian argument would take issue with allowing such political freedom to the people, as he believes only those with knowledge on issues should be allowed to take action regarding them.

To conclude, Schumpeter makes a compelling argument that competing elites are the best we can hope for in a democracy. Schumpeter is perfectly justified in making this claim, as he believes that this is the better compromise in order to achieve an effective form of government. Schumpeter’s model of democracy shows similarities towards a Platonic style of government, Max Weber’s vision of competitive elitism but mostly toward representative democracy, the model on which it is based. Schumpeter believes that a democracy is simply a method toward decision and that the populace should be happy to choose who they want to make such decisions, without having to make them themselves. Schumpeter’s theory therefore would be opposed by proponents of direct democracy such as Rousseau and would be criticised for not offering enough public participation. Although it is difficult to apply a theory like Schumpeter’s to contemporary society because of the relative contexts, it is easy to take the view that we are currently living in a similar system or at least one where we are represented by individuals. Although the elites in society are not so pre-determined, the electorate is still often left with a choice between just two realistic candidates for election. Despite this, representative democracy still lives strong today and does give the electorate a well exercised platform on which to scrutinise a government. On the whole we have very little problems with the current level of democracy, with governments remaining strong and decisive. According to Boucher, “Given what we know about human nature and its ability to exploit the institutional opportunities of government, a representative democracy with the appropriate liberal constitutional structure is the only appropriate way for the greatest happiness to emerge” (Boucher, 2009, p. 358). In my opinion a Schumpeterian theory is perhaps too extreme for today’s society and as such a representative form of democracy, from which Schumpeter’s theory stemmed, is probably the best we can hope for considering the repercussions of an alternative system.

Bibliography

Books

Boucher D. & Kelly P., (2009), Political Thinkers From Socrates to the Present, Second Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dahl R., (1989), Democracy and its Critics, London: Yale University Press.

Held D., (1987), Models of Democracy, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Phillips, (1993), Democracy and Difference, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Pitkin H., (1967), The Concept of Representation, London: University of California Press.

Saward M., (2007), Democracy, London: Routledge.

Schumpeter J., (1943), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Google Books [online], Available at: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6eM6YrMj46sC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Swedberg R., (1991), Joseph A. Schumpeter His Life and Work, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Journals

Cunningham S., (2010), ‘Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, socialism, and democracy’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, Volume 16, Issue 1, pp. 20-22.

Medding P., (1969), ‘Elitist Democracy: An Unsuccessful Critique of a Misunderstood Theory’, The Journal of Politics, Volume 31, No. 3, pp. 641-654.

Medearis J., (2002), ‘Joseph Schumpeter’s Two Theories of Democracy’, American Political Science Review, Volume 96, Issue 04, pp. 805-806.

Websites

J S. Mill, (1861), Representative Government, [online] Available at: http://www.constitution.org/jsm/rep_gov.htm.